|

|

Celebrating the 250th

Anniversary of the

French and Indian War: 1754-1763

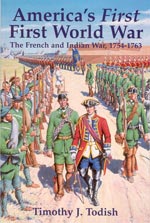

America's FIRST First World War

Tim J. Todish

We will soon be commemorating the 250th anniversary of the French and Indian War, and the next few years will undoubtedly see an increase in interest in this important but often forgotten conflict. Noted historian Lawrence Henry Gibson has written that this war "was destined to have the most momentous consequences to the American people of any war in which they have been engaged down to our own day . . . for it was to determine for centuries to come, if not for all time, what civilization-what governmental institutions, what social and economic patterns-would be paramount in North America."

When they initially began to colonize North America, the British were penned in along the Atlantic seacoast by the Appalachian Mountains. The French, on the other hand, were able to penetrate deeper into the heartland from their first colonies in eastern Canada because of their control of important waterways. Just as these two countries were rivals in Europe, so too were they destined to compete for control of North America. It is ironic that the person who set off the final conflict was none other than a young Virginia Provincial officer named George Washington.

In the fall of 1753, young Washington, already recognized as a skilled surveyor and hardy woodsman, led a difficult expedition to warn the French commander at Fort LeBoeuf in Western Pennsylvania that they were trespassing on Virginia territory and must leave immediately.

Not unexpectedly, the French politely declined, and the next year, Washington found himself in command of an expedition raised to drive them from the region by force. The primary objective was Fort Duquense, at present day Pittsburgh, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers combine into the mighty Ohio. Led by Indian guides, Washington and a portion of his force surrounded and surprised a party of French soldiers who were camped in a secluded glen not far from an area known as the Great Meadows. Washington's men opened fire, killing the French leader and several of his men.

The French retaliated by sending out a much stronger force against Washington's base camp at the Great Meadows, where the Virginians had hastily constructed a small fort aptly named Fort Necessity. After a brief battle, Washington was forced to surrender, and, ironically, on the fourth of July he marched his defeated army out of Fort Necessity. The French now were firmly in control of the Ohio Country. Although war was not formally declared until May 18, 1756, hostilities had begun, and they would eventually spread to almost every corner of the known world.

The early years of the war did not go well for the British. In July of 1755 an attempt to capture Fort Duquesne, led by British commander-in-chief General Edward Braddock himself, ended in bitter defeat. Contrary to popular myth, this battle was not a crafty French ambush of rigid British regulars marching stubbornly to their doom. For most of the march, the British moved cautiously and with adequate security. The battle did not open with an ambush, but rather it was a "meeting engagement" where the rapidly advancing French ran headlong into Braddock's advance guard. Both sides were equally surprised, and at first it appeared that British discipline and firepower would prevail. Soon the tide began to turn, however, as the French irregulars and their Indian allies began to work around the British flanks, unnerving the redcoats who were unaccustomed to forest warfare. With the collapse of the advance guard, the battle quickly turned into a route, with the British taking heavy casualties. George Washington, serving as one of Braddock's aides, was one of the few officers to escape unscathed.

Braddock's defeat largely overshadowed the year's British victories. In June, Colonel Robert Monckton captured Forts St. John and Beausejour in Canada, and in September, a Provincial army under William Johnson decisively defeated a force made up of predominantly French regulars under Baron Dieskau at the Battle of Lake George in New York State.

The French took the offensive in 1756 and in March they captured Fort Bull, a vital link on the supply line to Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario. The French commander in America, the Marquis de Montcalm, followed up by attacking and capturing Fort Oswego itself in August. The French victory was tarnished when French allied Indians were allowed to kill some of the surrendered British garrison.

The French would enjoy an equally successful year in 1757. Although the new British commander, Lord Loudoun, planned an aggressive strategy, a combination of logistical problems and bad weather prevented him from putting it into play. The French focused their efforts on the Lake George front. A difficult and daring winter attack on Fort William Henry was unsuccessful, but Montcalm returned later in the summer with a much larger force. After a determined defense, the outnumbered British garrison under Colonel George Monro surrendered on August 9 after being promised good terms. In a replay of what had happened at Fort Oswego the previous year, members of the paroled garrison were attacked and slaughtered by the French Indians as they were preparing to march to Fort Edward. This incident has been immortalized in the novel The Last of the Mohicans, which has been made into several movies and television productions.

The tide began to turn for the British in 1758, but not without one last serious defeat. General James Abercromby, who had replaced Loudoun as commander-in-chief, led a magnificent and seemingly invincible army against the French under Montcalm at Fort Carillon (or Ticonderoga) at the southern end of Lake Champlain. After the charismatic Lord Howe was killed in an opening skirmish, the British plan fell apart. Abercromby ordered a headlong attack on the French breastworks, and was driven off after suffering terrible losses.

Other British offensive campaigns for the year were more successful. Two brilliant young, newly appointed generals, Jeffery Amherst and James Wolfe, carried out a well planned siege against Fortress Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. By the end of July, this important seaport was in British hands. The third campaign, led by another two exceptional officers, General John Forbes and Colonel Henry Bouquet, was directed against Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio. This time, in the face of Forbes' cautious advance and overwhelming numbers, the French blew up and abandoned the fort that had cost so many British lives in 1755. By 1759, it was no longer a question of if the British would win, but simply a matter of when. The French were forced to adopt a purely defensive strategy, due in no small way to the neglect of the mother country. The British had three major goals. General Amherst, named commander-in-chief when Abercromby was recalled, carried out an almost bloodless campaign against Fort Ticonderoga. After capturing it in July, he moved northward to Fort St. Frederic, which the British called Crown Point. The badly outnumbered French retreated northward, leaving both Ticonderoga and St. Frederic in ruins.

After two senoir officers were killed, General William Johnson succeeded to command an expedition designed to retake Fort Oswego, and then capture crucial Fort Niagara at the juncture of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario. After what was primarily a textbook European siege, Fort Niagara capitulated in late July.

General James Wolfe's siege on Quebec was one of the greatest campaigns in North American history. He had the French capital fairly well bottled up throughout most of the summer, but for awhile it appeared that the approach of bad weather would force him to withdraw before taking the city. A number of lesser engagements were fought, and on July 31 the British suffered a major defeat in an unsuccessful amphibious assault on the French lines at Montmorency, east of the main city. Finally Wolfe decided that his only chance was a daring nighttime climb up the Heights of Abraham, where he hoped to force Montcalm to come out and fight in the open. Wolfe's plan worked. The French met him in open battle, and were soundly defeated. Both Wolfe and Montcalm received mortal wounds in the fighting, but Quebec was now in British hands.

Early in 1760, the new French commander, General Levis, attempted to retake Quebec, and nearly succeeded. He lured the British out onto the field where Montcalm had fallen the year before, and managed to beat them in open battle. The British, however, merely retreated back into the city, and Levis lacked the men and supplies to conduct a prolonged siege. He eventually fell back to Montreal, where he was soon surrounded by a well-planned three- pronged British pincer movement. He had no choice but to surrender, and with him fell all of New France.

The British victory was short lived, however. In 1763, a major Indian uprising led by the Ottawa chief Pontiac resulted in the loss of every fort west of Fort Pitt except Detroit. In another few years, the American colonies were in open revolt. Ironically, even the French commander Montcalm saw the danger on the horizon. Just before his death at Quebec, he wrote: "M. Wolfe, if he understands his trade, will take to beat and ruin me if we meet in fight. If he beats me here, France has lost America utterly: yes and one's only conclusion is, in ten years farther, America will be in revolt against England." The American spirit and love of freedom would not long tolerate British rule. And just as the Mexican War provided a training ground for the leaders who would eventually decide the course of the Civil War, so did the French and Indian War prepare many leaders on both sides for the roles they would play in our war for independence.

It is only fitting that during the coming 250th anniversary of these important events, we recognize the dedication and sacrifices of those on all sides of this conflict.

Examples

of Timothy J. Todish's Work

Click

image for more information.

ORDER NOW

|

|

|

|

Alamo

Sourcebook 1836:

|

|

FUTURE SHOW DATES

|

||||

|

March 15-16,

2008

|

• |

March 21-22,

2009

|

||

Copyright © 2007 Yankee Doodle Muzzle Loaders, Inc. All rights reserved.

This website may not be reproduced, in part or in whole, without the written permission

of Yankee Doodle Muzzle Loaders, Inc.

This web page is designed to be viewed best at 800 x 600 true color.

|

|

||

|

|

Weather

|

|

|